“Ghosts”

Our memories as much as our knowledge of the history plays a significant part in what triggers and starts our research into what we want to explore and consequently write about. There is ultimately some sort of haunting behind our writing of the past, be this in historiography or in literature. Colin Davis the author of the article “Ètat Prèsent: Hauntology, Spectres and Phantoms” discusses hauntology, a theory developed by Derrida with the word play on the word ontology, for its application in literature writing, I found this quote appropriate for discussing this particular art installations because it is as much a written as it is a visual narrative. Davis’s “figure of the ghost as that which is neither present nor absent, neither dead nor alive.” is addressed in the narrative which runs through my installation Monument: Her/story. Here the stories told belong to the ghosts of the events that haunt as well as the protagonists depicted in them. Everything is fleeting; people, places, no longer there, no longer substantial yet ever-present in the memories, the minds and lives of those survived. The inclusion of these stories of events, people and places in this narrative, documented in writing and presented in a country so far away from their origins also alludes to Davis’s comments regarding both ghosts being “a wholly irrecuperable intrusion in our world” and our responsibility to attend to the ghost being “an ethical injunction insofar as it occupies the place of the Levinasian Other {…} whose otherness we are responsible for preserving” (373).

This “ghost figure” is not only the specter that comes to “haunt” the present from the past, but it is also in the make-up of our memories. These may be memories we have inherited which are of events in the past experienced by our parents (postmemory) or memories of our own from past experiences, which some, we may also pass on to new generations in the future. The politics of memory Derrida talks about here meaning, the use and abuse of the way memory has been utilized within memory discourse and in its construction in order to keep certain discourses more alive at the expense of others, may indeed effect what is passed on.

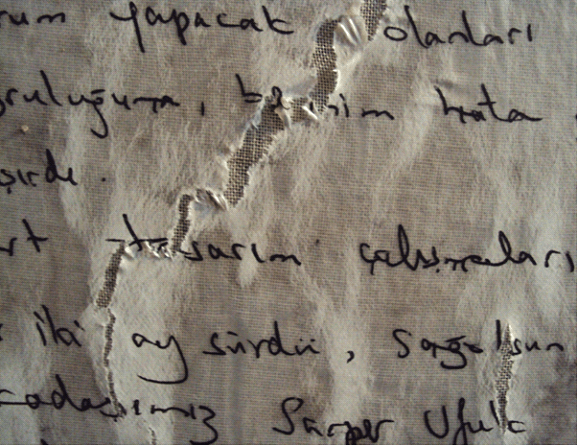

Memories are nevertheless what play a major role in our conducts when we try to take stock of the past in order to make sense for the present and the future. “Remembrance as a vital human activity shapes our links to the past and ways we remember define us in present” remarks Huyssen and continues: “as individuals and societies we need the past to construct and anchor our identities and to nurture a vision of future” (249). This is why as individuals, groups and nations we build monuments and keep archives. The main point of Derrida, in Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (1995) is “the question of the archive” not being a question of the past but “a question of the future itself” when he writes about “a response, of a promise and responsibility for tomorrow” (36) Derrida also states that the archive is related to the law and to the power of where it is kept. Where it is kept is also related to what is excluded, the determination of what is remembered and what is allowed to be forgotten. The other aspect of the archive is the organizing of our memories by writing them down, Derrida calls “hypomnesis’’ (19). This act of writing enables the remembering and forgetting to be stored. As the letters leave literal traces, the selected memory from the psyche separates and let it stand out as solidified evidence of experience which becomes a way of archiving.

This is precisely what Monument: Her/story claims and defends by my use of hand writing to depict the stories of the women in my life. In the quote; Derrida asserts that there is no sense in trying to avoid the spectral “other” which is always already plural; better instead to try and learn to deal and live with it. He suggests we try to accept the past and the otherness in it as well as we can and take the risk of welcoming the ‘ghost’ without expecting any gain. While agreeing with Derrida on this point in general, I also want to add that the apparition of the specter brings with it certain messages for us, therefore, the acceptance of the spectre/s necessitates a degree of trust in the messages we may receive from its absent presence in our lives.

Monuments, Nations and Ghosts

As if Addressing my enquiring questions, James E Young defines the traditional monument.

Traditionally, state-sponsored memory of a national past aims to affirm the righteousness of a nation’s birth, even its divine election. The matrix of a nation’s monuments traditionally emplots the story of ennobling events, of triumphs over barbarism, and recalls the martyrdom of those who gave their lives in the struggle for national existence-who, in the martyrologic refrain, died so that a country might live. In suggesting themselves as the indigenous, even geological outcrops in a national landscape, monuments tend to naturalize the values, ideals, and laws of the land itself. To do otherwise would be to undermine the very foundations of national legitimacy, of the state’s seemingly natural right to exist (270).

With this we understand that there is a parallel between who a nation is and why monuments are build.

Young also coined the term “counter-monument” in the 1990s in connection with the debates on contemporary monument concepts. Writing about Germany, Young thinks that the responsibility we have to remember the past can be fulfilled, to some extent, by the creation of counter-monuments by contemporary artists who are aware of this responsibility, but “aesthetically skeptical of the assumptions underpinning traditional memorial forms” (271). Having only postmemories of the Holocaust these young artists, he says, “explore both the necessity of memory and their incapacity to recall events they never experienced” (271). In their exploration they produce new forms of artistic expression which reflect both their relationship to and the distance from the actual events. As a result work is created which demands attention and reflection on the part of the viewer.

This idea of an ethical responsibility to remember underpinning the work of these artists, which also forces others to take part in the act of remembering, and therefore commemorating, has its parallel in Derrida and his idea of taking the risk to welcome the specter in order to build a more just future. It also resonates as an archival practice, both with surfaced memories of the viewers, and in some cases by the physical recording of memories in writing on the works themselves. I will come back to the question of whether or not my Monument: Her/story can be considered a counter-monument in this sense after a re-examination of my work in its own right and in relation to the other works exhibited at Avesta Art 2010.

Looking Deeper- Making Connections

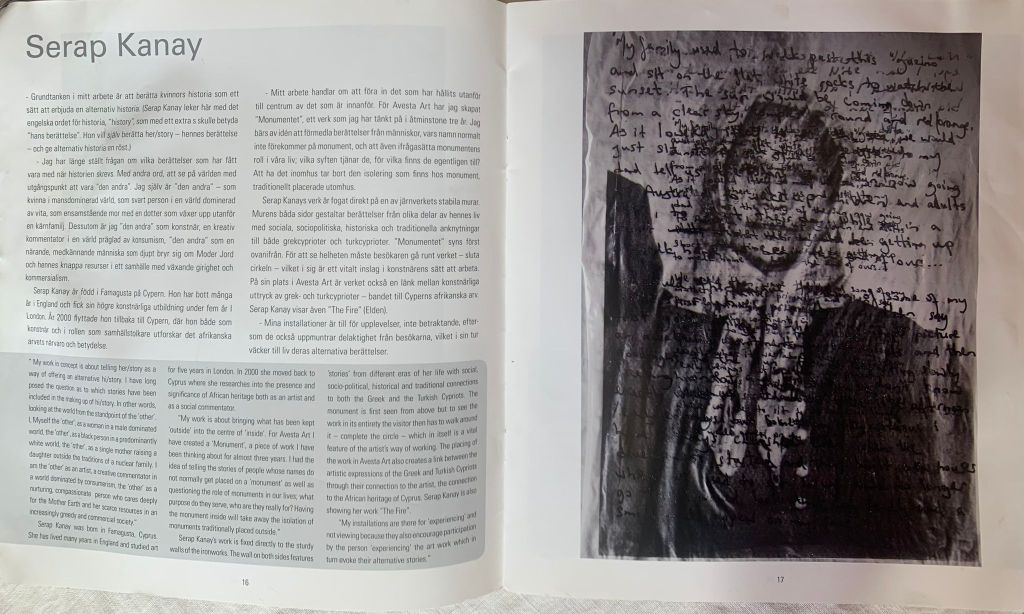

How does my installation work as a monument and what kind of monument is it? This is what I have said in the Avesta Art 2010 catalog:

My work is about bringing what has been kept ‘outside’ into the center of ‘inside’. For Avesta Art I have created a ‘Monument’, . . . I had the idea of telling the stories of people whose names do not normally get placed on a ‘monument’ as well as questioning the role of monuments in our lives; what purpose do they serve, who are they really for? Having the monument inside will take away the isolation of monuments traditionally placed outside (16).

There are two key concepts in this statement: bringing the outside in and telling the stories of people not normally placed on monuments, i.e. visibility and remembering. By claiming the sturdy, free standing wall of the ironworks as the monument inside I not only cut out the isolation of monuments placed outside in prominent busy places in towns where in time the local people pass by and not even remember what the monuments were for, but I also allowed the lives of ‘ordinary’ people come to light as agents as opposed to just names on traditional monuments that in time become invisible. The names placed on traditional monuments, with one or two exceptions, are erased from memory of whom they were supposed to honour. This invisibility spectralizes those names and the monument itself as a form. “The issue of remembrance and forgetting touches the core of Western identity, however multifaceted and diverse” remarks Huyssen (251). It is spectral to have monuments erected because the nation tries to remember the past, its sufferings and its heroes, then it forgets because of having erected so many of them. In the same vein, Young writes: “once we assign monumental form to memory, we have to some degree divested ourselves of the obligation to remember” (273 vellum ripped and crumpled in places set up, where guided t). In Avesta, having the monument inside reclaimed the visibility of both the monument I created and the people whose stories I depicted. The different layers of the media used, the slag-stone of the wall, the jotting iron pieces, the muslin (rusted in places), the photocopied ours were offered both about the history and the art placed in the ironworks of old Verket allowed for many spectres to be absent present at once for the different visitors.

Referring to Andreas Huyssen’s idea that “we suffer from an overload of memories” rather than “amnesia” and the monument which “had fallen on hard times in modernism is experiencing a revival” in the postmodern age (253). I Read Monument: Her/story in Avesta ART 2010 as not only spectralising the past in its content but also spectralising the monument in a form which was already spectralized by modernity and its revival in the 1980’s. The past is spectralized with the stories written from present reflections of the past events and the people in them. These reflections are results of memories reconstructed many a time through time and altered. The monument was already spectralized in its idea of being modern and being built in times of modernity. Huyssen says, “a modern monument is contradiction in terms” as to be truly modern means no links with the past, but then, although criticized the idea of building monuments came back (250). This coming back was also a way of spectralisation of the old structures. Installation as a form challenges the spectrality of the traditional monument itself. Monument: Her/story as an installation spectralized the already spectralized monument because it brings it in, it makes it temporary and it changes its form from an especially built massive structure which becomes invisible in its massiveness, to using a structure already from the past in an intimate space up in- your face. Then it depicts layers of different temporal and spatial occurrences entailing many hauntings which are bound to conjure up many spectres in a setting where both the stories and the idea of the monument is made visible to an expectant and enquiring public. The hand writing in my work was a feature that made the stories more accessible; it meant that they could be perceived as told stories. The use of black and white photographs, the photocopied original handwriting also gives a documentary feeling at the same instant as it confuses time; this authenticates and familiarizes the work, making it intimate and immediate. Moreover, exposed on the slag-stone walls of the ironworks Monument: Her/story carries traces of lived experiences known and unknowable. Within this, while conjuring many spectres and ghosts with its multiple layers, both in content and form, the work exposes the participant to a new ‘reading’ of historiography.

Thus, telling the told stories with written words on the monumental wall, there at Avesta ART 2010, laid claim to constructing an alternative archive with their visibility to “110 visitors a day on average” for 4 months (Linder). Does this also make my installation a counter-monument? Installation as a medium being a contemporary art form, the visitors being participants in the work can count Monument: Her/story in the category of a counter monument, but although some of the ‘stories’ depicted in the work are constructed from traces of memories, some are quite recent and, most importantly, their source is my memory even where I might have mediated some other people’s too. They are not postmemories like those used by the contemporary young German artists’ Young talks about. Monument: Her/story encourages the visitors’ undertaking of ethical responsibility while experiencing it, not unlike the counter-monument which “points to citizens’ everyday historical responsibility and ability to reflect” (Sigel). Yet, the other important difference is the temporality of my work as the works considered as counter-monuments still have permanence in their critical forms. Horst Hoheisel’s “negative form monument” in Kassel which was conceived in 1987 as a monument for “Aschrott’s Fountain” or Christian Boltanski’s Empty House in Berlin can be seen as examples of this permanence. Monument: Her/story is a site-specific installation which becomes redundant at the end of the duration of a show, however long or short. As the original writing can be added to and photocopied, it can be installed in another site for any duration, taking in new participants and new reflections and calling on different ghosts. As part of my artistic quest to emphasize an alternative history I would like to think of Monument: Her/story as an alternative monument which lays claim to an alternative archive that questions the form and the content of both the monument and the archive in its existence alongside them.